So, what is this scale you speak of?

Simply put, it is one of the most irritating nuisances a tea-enthusiast will face.

It makes your water--and thus your tea--taste like clay (not that I have any experience in the clay-eating department), and it is notoriously difficult to prevent or eliminate.

It makes your water--and thus your tea--taste like clay (not that I have any experience in the clay-eating department), and it is notoriously difficult to prevent or eliminate.Scale is more specifically described as calcium carbonate (CaCO3, see right). It is the same thing found in chalk, insect and shellfish shells, and limestone. Calcium carbonate isn't all bad, as it is often used in dietary calcium supplements and antacids. Still, it doesn't taste great, so I'd get your dietary calcium somewhere other than your tea water if I were you.

A day in the life of hard water

Scale deposits are formed as a result of chemical reactions in hard water. So, to understand how best to remove scale, let's take a look at this process.

Underground water aquifers are exposed to significantly elevated amounts of CO2. As this carbon dioxide-rich water trickles through calcium carbonate-containing rock (such as limestone), the calcium carbonate is dissolved. Calcium carbonate is quite insoluble, so it must be converted to calcium bicarbonate in order to dissolve in water. This occurs naturally when there is a large amount of carbon dioxide present, and follows this reaction:

Rxn 1: CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O → Ca(HCO3)2

This water is now what we would call "hard" water. (Hard water also contains other minerals, but for our purposes we will ignore them.) When this water is drawn from the faucet, it is suddenly in the presence of much less CO2 than it was while in its aquifer. As there is less carbon dioxide present, the exact same reaction will run in reverse:

Rxn 2: Ca(HCO3)2 → CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O

This is what causes calcium carbonate (scale) to precipitate out of hard water. (Notably, this reaction also causes the formation of stalactites and stalagmites in caves)

This is what causes calcium carbonate (scale) to precipitate out of hard water. (Notably, this reaction also causes the formation of stalactites and stalagmites in caves)So, why do you find more scale deposits in your kettle than in your teapot? It is a common misconception that scale's solubility is directly related to water temperature. Calcium carbonate is hardly soluble at any temperature, cold or hot, but calcium bicarbonate is. And what do we need in order to form calcium bicarbonate? Calcium carbonate and carbon dioxide.

The solubility of gases, such as carbon dioxide, decreases as the temperature of water rises. So, when you boil your water in a kettle, the amount of dissolved carbon dioxide decreases. The chemical equation shown above will try to restore equilibrium, so more calcium bicarbonate will be converted back into carbon dioxide, water, and calcium carbonate. This increased amount of calcium carbonate precipitates out of solution and forms scale deposits.

Shedding your scale

Now that I have shown you the chemistry of scale deposit formation in exhaustive detail (Isn't chemistry fun?), I will explain how to remove those dreaded deposits.

Let's take the same equation as above, but slightly rephrase it:

CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O ⇌ Ca2+ + 2 HCO3-

(Notice that there is now a ⇌. This signifies that the reaction proceeds in both directions. Earlier I used a plain arrow to illustrate a point, but I'll use proper notation now. Also, instead of "Ca(HCO3)2" you now see "Ca2+ + 2 HCO3-." These both mean the same thing, but in reality calcium bicarbonate splits into two ions when in solution, as reflected in this equation.)

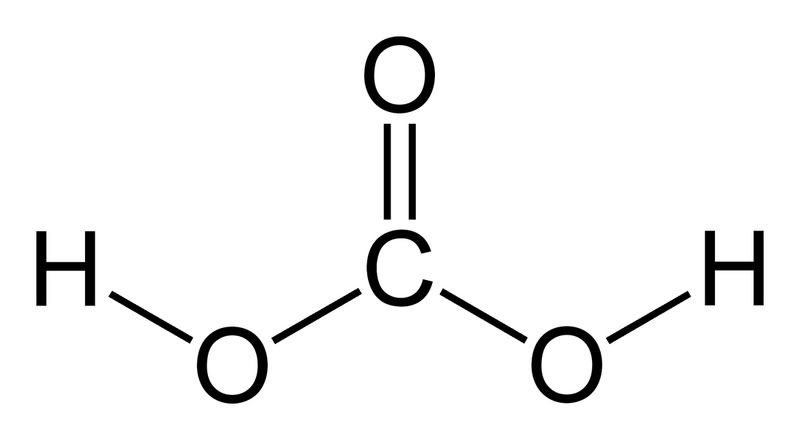

If you don't have much background in chemistry, you may or may not have heard of the term "conjugate base." The bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) is an example of a conjugate base (its conjugate acid being carbonic acid, H2CO3, shown right). Bases act by abstracting H+ ions from acids. By adding an acid stronger than carbonic acid, the bicarbonate ions will take up hydrogen, and thus there will be very few lone bicarbonate ions left in solution.

If you don't have much background in chemistry, you may or may not have heard of the term "conjugate base." The bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) is an example of a conjugate base (its conjugate acid being carbonic acid, H2CO3, shown right). Bases act by abstracting H+ ions from acids. By adding an acid stronger than carbonic acid, the bicarbonate ions will take up hydrogen, and thus there will be very few lone bicarbonate ions left in solution. Example: HCl + HCO3- → Cl- + H2CO3

This loss of bicarbonate ions will drive the above reaction toward making more bicarbonate ion, which will also take up H+, and the reaction will continue until there is no more CaCO3 left. *Poof!* No more scale!

So, the take home message is: Strong acid will eliminate scale.

Weighing your descaling options

There are other ways of dissolving scale, but acids are the most cost-effective method and does a very good job for the tea-enthusiast's needs.

There are several common household products that fall into these categories, such as vinegar (acetic acid) and citrus juice (citric acid). You can also purchase descaling products made from a variety of acids (such as maleic acid, sulfamic acid, etc.) specifically made for tea and coffee equipment. Just heat up whatever acid you're going to use and soak your affected teaware overnight. Any of these acids should work, but the descaling tablets may work faster, so the choice is really up to you.

There are several common household products that fall into these categories, such as vinegar (acetic acid) and citrus juice (citric acid). You can also purchase descaling products made from a variety of acids (such as maleic acid, sulfamic acid, etc.) specifically made for tea and coffee equipment. Just heat up whatever acid you're going to use and soak your affected teaware overnight. Any of these acids should work, but the descaling tablets may work faster, so the choice is really up to you.***Unrelated fact: The latin name for orange is citrus sinensis, and the latin name for tea is camellia sinensis. "Sinensis" translates as "Chinese."***

Warning about descaling your teaware

Be careful what descaling products you use on porous teaware. Using vinegar or citrus juice on a Yixing pot could very well ruin the pot, as the flavors and aromas may be absorbed into the clay. So, be cautious and use your common sense.

Final words

Scale is definitely annoying, and tastes awful. Luckily, it can be dissolved with minimal effort if you use the right products, and you can go right back to drinking your favorite teas!

[Edit: Thanks Salsero, I knew I forgot something. You don't really need to know any of the chemistry, so don't worry. As for how much vinegar or how long you should apply it, I'm not really sure. I just use descaler tablets because I find the smell of vinegar, especially heated vinegar, to be quite repulsive. I would think a dilution of one part plain ol' distilled vinegar (no reason to use the fancy stuff) to one or two parts water should do the trick, though. Just heat it up to around 140-150°F and let it soak for a few hours or overnight. If that doesn't work, either try it again with a stronger dilution or go buy some descaler tablets. They're more powerful (they can damage your skin if you make contact, so be careful), but they usually come with instructions so you know that you're doing it right. Hope this helps!]

References:

Wikipedia: Calcium carbonate, Hard water, Carbonic acid, and Orange (fruit).

Wow. That's a great post. Your style and humor make the chemistry very accessible. I bet my 13-yr-old brother could read it and understand perfectly. I loved the asides (oranges and teas...oh Linnaeus, there was method to your, er, method!) and appreciated that you investigated other scale-removal products than the much-beloved vinegar. Rock on!

ReplyDeleteMy eyeballs glaze over at the first sight of a chemistry equation. Please, for the 99% of commoners out here, bottom line it. How much vinegar, how long, how hot. Cookbook style!

ReplyDeleteI would have to agree with Mary R. this was a informative read! I will never look at the white stuff handing from my facet head the same again! LOL

ReplyDeleteGood Post!

Thanking you for bringing it all back home for the non-scientists who surround you!

ReplyDelete